Throughout his 70 year-long career, Stan Lee (1922-2018) created many of the major comic book superheroes that are known throughout the world. He introduced us to a diverse array of characters with varying degrees of superpowers and complex personal narratives, such as Spider Man, The Black Panther and the mutant collective known as the X-Men.

Lee’s work in comics impacts our collective culture in a manner that goes above and beyond mere entertainment. Through the many comics that he published under his company, Marvel Comics, Lee has inspired generations of children, adolescents and adults to think critically, develop their literacy skills and expand their imaginations. His comic books are embedded with real life issues, which makes his otherwise superhuman characters appear approachable and….well, human. In Lee’s comic book universe, traditional linear storytelling and simple dualities are turned upside down and revised to reflect a more Humanist form of fiction. His comic book stories surpass the obvious tried and true tale of good vs. evil and right vs. wrong, where the bad character(s) commits a crime, which the good character(s) solves. Instead, the Marvel characters and their associated problems represent similar multifaceted issues that we all face in our daily lives. Issues such as race, gender, violence, corruption and authoritative governments, are common causes for the characters in Marvel Comics to grapple with. The typical ‘good-guys’ and ‘villains’ are actually well-rounded individuals with traits that are both admirable and problematic. This is because Stan Lee incorporated very humanizing elements into each character that he introduced into the realm of visual culture.

For example, Magneto, the main adversary that the X-Men faced, was once an ally and collaborator of Dr. Charles Xavier (Professor X), the founder of the school for mutants that supports the X-Men. Both individuals are portrayed as influential leaders who stand up for the rights of marginalized groups, however, their methods of working towards achieving this goal are in stark contrast with one another. While they are each important advocates for mutant rights (which can be interpreted as being symbolic of all marginalized groups within society), Professor X calls for a diplomatic approach of integrating mutants and non-mutants together, while Magneto calls for the use of force against non-mutants, who have treated the mutants as second-class citizens. Parallels to historical and current events and figures can be made using the two ideologies to express different forms of activism and sociopolitical organization. For example, some critics have suggested that they are both inspired by historical Civil Rights leaders. Dr. Xavier is inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, while Magneto has been compared to Malcolm X (Godski, 2011). Lee’s narratives regarding the relationship between Magneto and the X-Men tread carefully as to not express moral superiority of one ideology over another. Instead, the characters are portrayed in an open-ended manner, which is indicative of multiple social, cultural and political thoughts. Lee himself stated that he “did not think of Magneto as a bad guy. He just wanted to strike back at the people who were so bigoted and racist… he was trying to defend the mutants, and because society was not treating them fairly he was going to teach society a lesson. He was a danger of course… but I never thought of him as a villain.”

Blurring fiction and non-fiction is something that makes Marvel Comics a socially engaged form of art and literature. Stan Lee and his collaborators kept their comics relevant with the times, which is poignantly evident in the creation and development of Captain America. Captain America is a patriotic hero, introduced during WWII, who initially defeated Fascist regimes and embraced the progressive idea of multiculturalism. However, over the course of the comic’s ongoing story line there have been ominous warnings that patriotism could lead to the same oppressive ideologies that Captain America opposed. At one point, Captain America represented zealous Nationalism and right-wing propaganda. This happened when Captain America’s original alter-ego, Steve Rogers, had taken a hiatus (he was thought to have been dead) from society and Captain America’s persona was taken on by an admirer named William Burnside. Through Burnside, Captain America embodied a darker side of patriotism. Burnside represented all that could go awry when blindly led by specific dogmatic ideologies in lieu of facts, critical thinking and empathy.

While Captain America addressed Fascism, Lee’s character, The Black Panther, took on racism. The Black Panther character was introduced in 1966, which makes him the first black superhero in mainstream comic book culture. The complex and compelling narrative of the Black Panther was inspired by the Afrofuturist genre, where the culture of the African diaspora is combined with fantasy, sci-fi, historical fiction and non-Western metaphysics. Afrofuturism envisions a world that overcomes White Supremacy and oppression of Africans by Western forces. In the Black Panther series, the protagonist is T’Challa, the king and guardian of a fictional African nation called Wakanda. Wakanda is a thriving nation where scientific advances go above and beyond the scope of the science introduced by Western civilization. Most significantly, Wakanda is a place where blackness is celebrated and issues such as discrimination and racism are confronted directly. When the comic book character was adapted into a film in early 2018, an educator by the name of Tess Raser, designed and implemented a curriculum around the major themes (multiculturalism, feminism, racism, scientific progress, etc.) of the Black Panther narrative.

In addition to encouraging social justice, diversity and critical thinking, Lee was an advocate of visual literacy. In 2010 he formed the Stan Lee Foundation in order to bring attention to the integration of literacy, pedagogy and the arts. The mission of the foundation is to support programming and methodologies that expand student’s access to literacy resources that promote cultural diversity. The fact that Lee was a strong supporter of literacy is not surprising, considering that comic books and graphic novels provide an excellent framework for developing and strengthening reading and creativity. Because comic books combine visual and written language, they’re a prime resource for learning to make associations between language and other forms of expression. This can be especially beneficial for students who are emergent language learners (or developing bi-lingual learners) because the sequential narratives within comics are presented in an accessible manner that uses symbolic and descriptive imagery to bolster the written dialogue.

As a result of the wide range of themes and symbolism present in comic books, several contemporary artists have been attracted to them. Artwork by artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Linda Stein, Raymond Pettibon, Chitra Ganesh, re-present comic book imagery in order to address contemporary sociocultural themes.

When assessing his prior artistic experiences, Jean-Michel Basquiat stated “I was a really lousy artist as a kid. Too abstract expressionist…really messy. I’d never win painting contests. I remember losing to a guy who did a perfect Spiderman.” Despite this claim, Basquiat developed a highly personal database of symbolic imagery, which is as iconic as the Marvel (and D.C.) comic book characters that inspired him. While comic book superheroes make up a relatively small part of his prolific oeuvre, it is obvious that Stan Lee’s creations represented an important part of Basquiat’s artistic development.

Basquiat’s use of superheroes in his paintings make connections and create new meaning around issues of intersectional identity. Basquiat’s incorporation of different sources from popular culture, visual culture and history, reflected his poignant responses to the pandemic of bigotry and violence against black individuals. The superheroes in his paintings included both fictional Marvel (and D.C.) comic book characters, as well as real-life African American influences such as Mohammad Ali and Charlie Parker. Basquiat’s heroes are both triumphant and tragic and embody the many trials and tribulations of black culture within the American landscape.

While satire and political critique have ancient roots (see: Elliot, 2004), the origin of the comics as a socially engaged visual artform dates back to the 18th century in England, where individuals like William Hogarth and James Gillray created the precursor to the modern comic strip. Hogarth’s series of politically inspired satire was called “modern moral subjects,” his most famous of which included A Harlot’s Progress, A Rake’s Progress and Marriage A-la-Mode. Gillray was a renowned caricaturist, who famously created burlesque criticisms of authoritative figures such as King George III (see: Farmer George and his Wife) and Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1841, Henry Mayhew and Ebenezer Landells founded a magazine called Punch, which mass produced politically charged comics by a variety of artists. The magazine was highly successful and lasted until 1992.

Hogarth, Gillray, Mayhew and Landells’ work inspired many other artists to take a socially conscious approach to their work. For example, Thomas Nast, one of the seminal American satirists of the 19th century used the power of visual imagery to make sweeping statements about corruption. His 1874 wood-engraving Jewels Among Swine, which depicts the police as swine with batons, engaging affably with gangsters, while arresting women activists that were protesting against the lack of enforcement against crime. This graphic style of shocking and captivating satirical narration is evident in the work of many contemporary artists such as Spain Rodriguez and Raymond Pettibon.

Rodriguez’s inspirations came from underground comix scene (see: Estren, 1974), motorcycle culture and progressive politics. His 1969 comic strip Manning, is a film noir inspired narrative of a crooked detective who takes little issue with using his authority to lie, cheat, steal and brutalize innocent civilians. The graphic nature of Rodriguez’s art is reminiscent of modern comic book artists such as EC Comics‘ Wally Wood.

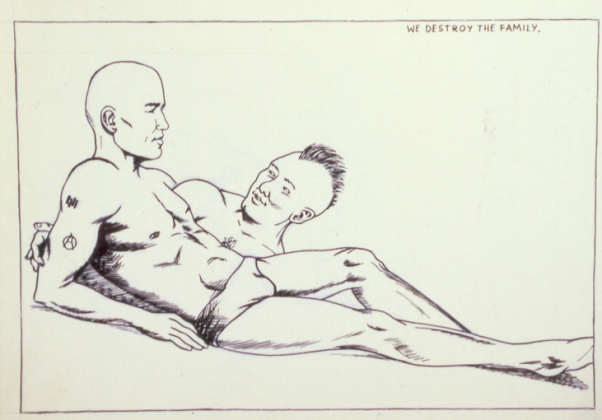

Raymond Pettibon’s artistic origins manifested within the punk rock music scene during the late 1970s. He made artwork, zines and album covers for punk bands such as Black Flag. Pettibon’s unique style of brash line drawing combined with symbolic text, poignantly connect fine art with popular and underground visual culture. His drawings establish a contemporary dialog with the socially charged political cartoons of Thomas Nast and the expressive art of Goya (among others). Pettibon frames his imagery in a novel way that references both past and present narratives while consciously leaving room for interpretation. As an artist whose inspiration frequently is derived via comic book culture, Pettibon uses the comic strip format to deconstruct certain sociocultural frameworks (see: Zucker, 2017). For example, comic book icons depicted as homosexual lovers (Batman and Robin), or his 1983 drawing No Title (We destroy the), can be interpreted as a mocking rebuttal to Fredric Wertham’s condemnation of comic books as being degrading to culture because of sexually suggestive themes (see: Wartham’s Seduction of the Innocent, 1954).

Linda Stein and Chitra Ganesh each implement comic book styles and themes into their artworks, which focus on the intersectionality of identity and systemic marginalization. Linda Stein portrays archetypal superhero symbolism and iconic characters to comment on the strength, audacity, vitality and perseverance of ‘the other’ throughout history. Steins Knights of Protection series (2002-) is inspired by armor and uniforms worn by superheroes and other powerful figures throughout time. These “androgynous sentinel-like figures” are intended to stand guard against oppressive and demeaning forces. Stein also creates wearable sculptures, which she calls Body Swapping Armor (2007-) that embody guardian-like qualities and give the wearer a sense of self and collective value. Some of the symbols on these protective suits resemble insignia affixed to the outfits worn by comic book heroes. In addition to her sculpture, Stein’s ongoing mixed-media series Superheroes, Icons, and Fantasy Females (2007-), appropriates the likeness of women from comic books to question what makes a hero and address stereotypical gender references in popular culture.

Chitra Ganesh’s artwork articulates new meanings from both personal and recorded history and mythology in order to address gaps in collective storytelling. Similar to the Afrofuturist movement, Ganesh’s work envisions alternative multicultural scenarios, where gender, sexuality, race and spirituality are re-presented in a nonlinear fluid state that is devoid of preconceived identity constructs and hierarchical structures. Many of her artworks take the recognizable format of comic books, although Ganesh is much more interested in creating open-ended dialogue than with presenting a sequential narration. She stated:

Much of my visual vocabulary across media engages the term ‘junglee’ (literally ‘of the jungle’, connoting wildness and impropriety), an old colonial Indian idiom (still) used to describe women perceived as defiant or transgressing convention. I’m deeply indebted to and inspired by feminist writing that dismantles traditional structures in favor of radical experiments with translation and form including that of Clarice Lispector, Anne Carson, and books like Mrs. Dalloway, and Beloved. In layering disparate materials and visual languages, I aim to create alternative models of sexuality and power, in a world where untold stories keep rising to the surface.

Because of the previously described social, emotional and cultural connections within comics (and the work of visual artists inspired by comic culture) and their strong ties to literacy, comic culture should be recognized, studied and widely utilized in the educational sphere. In 2001, Michael Blitz organized The Comic Book Project, which supports curricular connections between the visual arts and language arts. When the project was initially implemented at a public elementary school in Queens, New York, many of the students responded to the task of making a personal comic strip by depicting specific social issues that they experience on a daily basis within the urban environment. The benefits of the students’ engagement with the comic book genre included a noticeable increase in artistic and literacy development, as well as a strong sense of efficacy, social awareness and empathy (Blitz, 2004).

Additionally, comics and graphic novels (a comic inspired long-form book) are a great accompaniment to history and social studies curricula. The aforementioned Marvel comic book characters such as the X-Men (Civil Rights and Holocaust studies), Captain America (immigration and fascism) and the Black Panther (multiculturalism, the African diaspora and racism), each provide elements of historical fiction that can be analyzed and discussed as students learn about related historical accounts.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, is an essential graphic novel that tells a heartfelt and harrowing story about surviving the Holocaust; while John Lewis and Andrew Aydin’s graphic novel March, expresses a jarring and uplifting account of the Civil Rights era. Like Spain Rodriguez, Spiegelman got his start in the underground comix scene. After listening to primary accounts of his father’s experiences during Holocaust, Spiegelman created a moving tale of the Jewish people’s struggle for survival during the Nazi regime’s reign of terror. In Maus, Spiegelman symbolically represented the Jewish people as mice and the Nazis as cats. In March, John Lewis tells his own biographical story as an activist during the 1960s Civil Rights movement, which ultimately forged his path towards becoming a United States congressman.

Stan Lee’s legacy lives on in everyone who opens up a comic book and feels empowered to live, love and learn through the socially engaged content. While we’re unlikely to develop superhuman powers, it is our human elements (which happen to also be Studio Habits of Mind) such as exhibiting empathy, thinking critically (self-reflection and assessing our actions) and taking bold actions to confront difficult situations, that might just save the day.

References, Notes, Suggested Reading:

Blitz, Michael. (2004). “The Comic Book Project: The Lives of Urban Youth.” Art Education, 57 (2), 33-39.

Bitz, Michael. (2004). “The Comic Book Project: Forging alternative pathways to literacy.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 47 (7), 574-588.

Dittmer, Jason. (2013). Captain America and the Nationalist Superhero: Metaphors, Narratives, and Geopolitics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Elliott, Robert C. (2004). “The nature of satire”, Encyclopædia Britannica.

Estren, Mark James. (1974 and 1992). A History of Underground Comics. New York: Straight Arrow Books/Simon and Schuster, 1974; revised ed., Berkley: Ronin publishing, 1992.

Godoski, Andrew. (2011). “Professor X And Magneto: Allegories For Martin Luther King, Jr. And Malcolm X”. Screened. Archived from the original on 2011-06-18. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

Johnson, Jason. “How Stan Lee, Creator of Black Panther, Taught a Generation of Black Nerds About Race, Art and Activism.” The Root. 13 Nov. 2018. https://www.theroot.com/how-stan-lee-creator-of-black-panther-taught-a-genera-1830406797

Taylor, Paco. “Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Artwork Reveals Powerful Superhero Influences.” 28 Sept. 2018, Medium. https://medium.com/@StPaco/artist-jean-michel-basquiats-artwork-reveals-powerful-superhero-influences-811a1c6673e7?fbclid=IwAR0khXZe5UCcUzJlpsfsUfNY1ZIX27Tm6slItFKLapECOc3Lspf8F9vOS1g

Zucker, Adam. “Raymond Pettibon: Visual Vehemence.” Rhino Horn. 20 Feb. 2017. https://rhinohornartists.wordpress.com/2017/02/20/raymond-pettibon-visual-vehemence/

Thanks for liking my post so I got to read yours….I like how you think

LikeLike

Thank you Marilyn, I am honored to read your kind reply! I am very inspired by the beautiful creative endeavors you and your students are experiencing together! I look forward to keeping in touch. Thanks again for reading my post 🙂

LikeLike

Adam..you have been a breath of fresh air to an old teaching artist…I gobble up every thing you publish

thanks Marilyn

LikeLiked by 1 person